Teaching attention, part 3 / N: Thinking more creatively

To this point, our memory mechanisms all have had the same flavor. We had a running summary \(h_t\), which we update with every new input, though gating might mean we prevent some coordinates from changing too much. However, it’s possible to think more creatively about how we should record and attend to new memories. For example,

- We don’t need to throw away all but the last \(h_t\) when making some prediction. We’ve been saying that a model “forgets” if there are values for \(h_t\) early on which are erased by new inputs. But what if we just kept all the \(h_t\)’s, and avoided overload by having a smart lookup strategy?

- Why are we forcing the memory \(h_t\) to architecturally mirror the inputs \(x_t\) – that is, why does \(h_t\) need to be a sequence? Considering that, due to gating, we only update some cells at a time, it makes sense to design architectures specifically adapted to recording and looking up useful summaries.

- We’ve assumed a pretty diligent sequential processor, which knows to check every input datapoint as it arrives. What if we had a lazy one, which played it fast and loose and tried to process only those inputs that seemed really crucial to the process.

These sorts of preposterous questions will help illuminate the more fundamental principles of memory and attention in deep learning1.

First though, a warning, reiterating points from part 1. Attention is not a well-defined, clearly demarcated mathematical term. It is a principle that is useful for reasoning about many problems, but which is always in flux, as people find variants that are suited to their particular settings.

To keep our discussion grounded, and to leave you with something mathematical examples (and not just cool paper titles) that you can take home, we’re going to explore a few attention mechanisms in detail, before briefly touring across other highlights of the memory and attention literature.

Our three methods mirror the three questions from before.

Attention in Translation Models

We don’t need to force \(h_t\) to condense everything from \(x_1, \dots, x_t\). This observation lies at the heart of attention-based encoder-decoder sequence translation models. Before explaining the mechanism in more detail, a refresher on how translation works with neural networks.

Abstractly, the problem of translation is to map a sequence of words in one language to the corresponding sequence in another. For example,

I don’t speak French –> Je ne parle pas le Francais.

We make this an ML problem by treating each word as a datapoint in a sequence, and hoping to map the first trajectory into the second. That is, we want to map

\[\begin{align} \left(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4\right) \to \left(y_1, y_2, y_3, y_4, y_5, y_6\right) \end{align}\]where \(x_i = \left(0, \dots, 0, 1, 0, \dots, 0\right)\) is a one-hot encoding of the \(i^{th}\) word in the sentence (with respect to the \(V\) words in English that we bother taking into account), and \(y_i\) does the same for French.

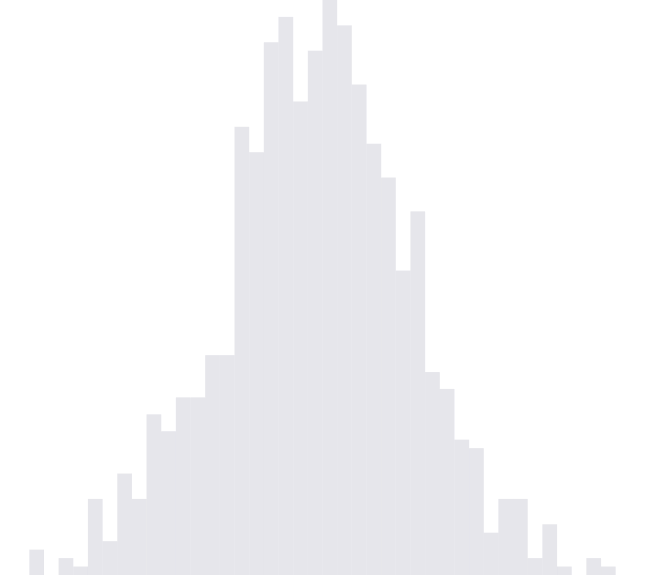

The encoder-decoder approach to the problem is to take the \(x_t\) and summarize (“encode”) them using an RNN2. The final state $h_{T}$ is then used as the used as the initial state to a separate RNN, whose states are used to predict the words of the translation. Here’s a basic picture. The shading means that teh same values are copied over.

At the \(t^{th}\) time step during decoding, we use a processor \(s_t = f_{\text{dec}}\left(\hat{y}_{t - 1}, h_{t - 1}\right)\), and then predict \(p\left(y_t \vert s_t, s_{0}, \hat{y}_{t - 1}\right)\) using logistic regression. A good processor should be able to capture the salient features of \(x_1, \dots, x_{T}\), and these are used for translation.

This seems like a large burden for the encoder to carry. Intuitively, at time \(t\) of decoding, you really only care about the words in the corresponding neigorhood of time \(t\) in the source sentence. If the sentences were already aligned, you’d expect the neighborhood around \(h_t\) to be most relevant for being able to translate \(y_t\).

So, consider the mechanism, \(s_{t^{\prime}} = \sum_{t = 1}^{T} w_{t t^{\prime}} h_t\), which adds columns \(h_t\) weighted by \(w_t t^{prime}\)’s, which we call attention weights. Of course, we need the \(w_{tt^{\prime}}\)’s to be learned directly from data – this is the same problem as in gatings. The solution shouldn’t be a surprise: we use a differentiable, parameterized function. For example, we could use

\[\begin{align} w_{t t^{\prime}} \propto a_{W_{a}}\left(h_t, s_{t^{\prime}}\right) = h_t^{T} W_{a} s_{t^{\prime}} \end{align}\]to measure the angle between particular coordinates of the encodings.

It’s worth highlighting what doesn’t directly appear in this definition – the times \(t\) and \(t^{\prime}\) themselves. This version of attention is a purely “content-based” form of attention, which cares only about the encodings \(h_t\) and \(s_t^{\prime}\). There are variants that take the times themselves into account, so that the decoding at time \(t^{\prime}\) explicitly upweights encodings at around that time in the original sequence2.

There are a lot of moving parts here – an encoder, a decoder, and an attention module to link them together. But everything is end-to-end differentiable, and you can take the gradients of mistranslations with respect to all parameters.

Stepping back, this is a way of reweighting – or attending to – specific encodings as a function of our current position in the decoding task at hand. We have provided some much needed relief for our lone encoder by more richly relating elements of our differentiable system. We no longer need a processor that compresses everything into one statistic \(h_{T}\) because we have a more sophisticated way of navigating a large collection of summaries and pulling out what is useful.

This kind of search for locally relevant information is a hallmark of attention mechanisms. More specifically, this pattern of breaking a task into pieces \(t^{\prime}\) and finding a way to learn different distributions \(w_{\cdot t^{\prime}}\) over relevant summaries is one that appears througout the literature on soft-attention mechanisms.

Neural Turing Machines

This discussion suggests that more carefully structured (if potentially intricate) mechanisms for looking thigns up can alleviate problems of remembering information that was introduced long ago. This is actually a general principle, not just some quirk about encoder-decoder architectures. To illustrate this, we consider the Neural Turing Machine.

Again, there is a bit going on. The diagram below introduces the cast of characters.

Given new input, we produce a weight distribution for what seem like the most relevant memory locations. Notice that if the rows correspond to times \(1, \dots, T\), then the matrix \(M\) is a lot like a stacked version of the \(h_1, \dots, h_T\) from the RNN models before. And, the \(w_{t}\)’s do seem eerily like the attention weights from before. That said, we’re trying to free ourselves from the idea that memories must be indexed by time.

In this spirit of generalization, we can define soft-attention variant,

\[\begin{align} r_t &= \sum_{i} w_{ti} M\left[i, :\right]. \end{align}\]Something in this architecture which is new, and not just a variant of what we saw before in translation, is a notion of writing to memory. We use weights, along with the add and erase vectors, to define a memory update,

\(\begin{align} M\left[i: \right] \xleftarrow M\left[i, :\right] + w_{ti}\left(a_t - e_t \circ M\left[i, :\right]\right). \end{align}\) If the weight is small, we don’t change that location in memory at all. If it is large, we add in \(a_t\) and erase everything that had been at that row, with an aggressiveness controlled by \(e_t\) (coordinates where that vector is near \(1\) are almost entirely reset).

The only remaining issue is how to figure out a good combination of parameters \(w_t, a_t\), and \(e_t\), upon seeing a new input \(x_t\).

Kris at 09:12